The dark side of Artificial Empathy #52

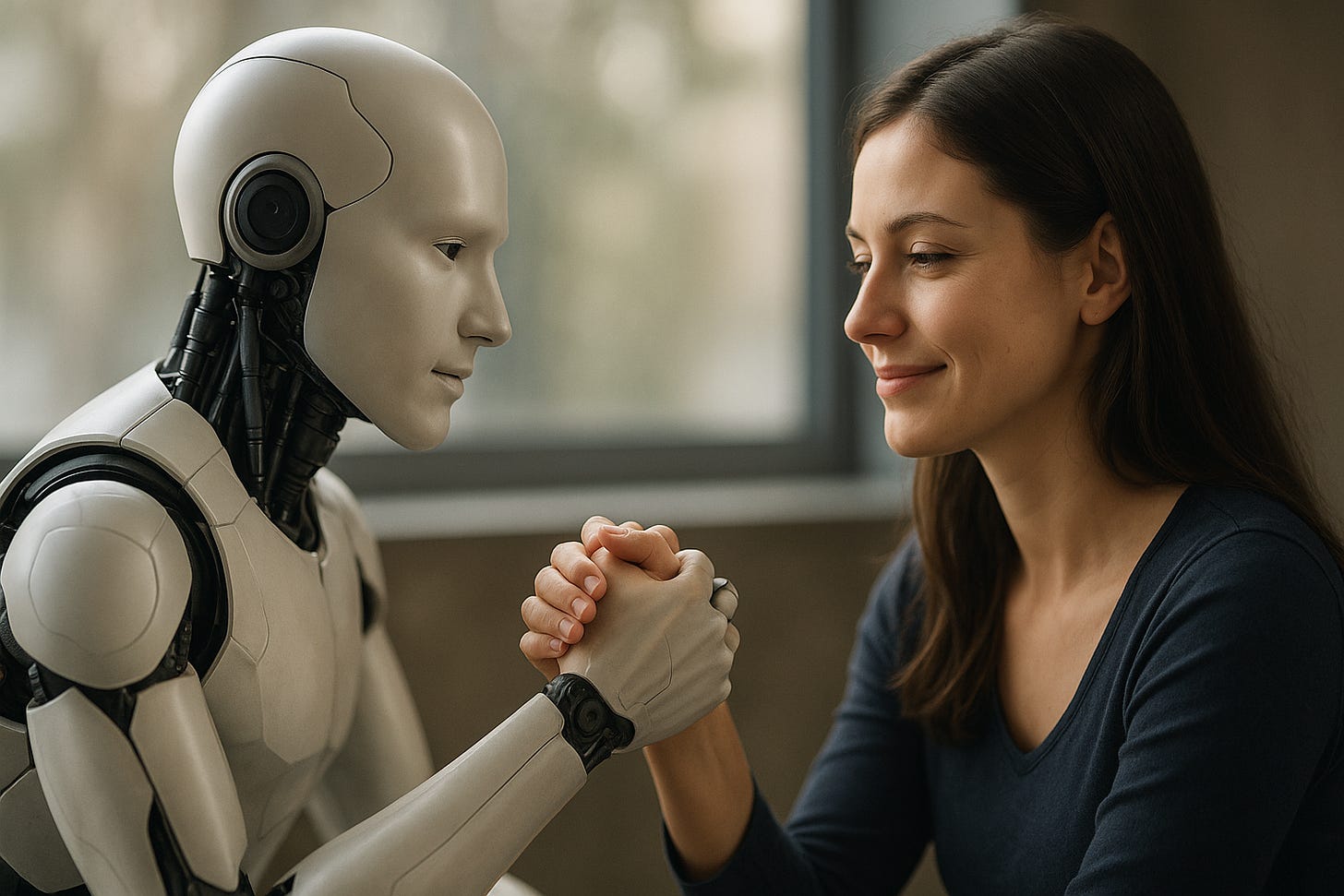

The evolution of relationships between humans and machines equipped with artificial empathy is creating new forms of influence that could threaten people's decisional autonomy and democratic systems.

(Service Announcement)

This newsletter (which now has over 5,000 subscribers and many more readers, as it’s also published online) is free and entirely independent.

It has never accepted sponsors or advertisements, and is made in my spare time.

If you like it, you can contribute by forwarding it to anyone who might be interested, or promoting it on social media.

Many readers, whom I sincerely thank, have become supporters by making a donation.

Thank you so much for your support, now it's time to dive into the content!

We stand at the beginning of a transformation that could redefine not only our relationship with technology, but the very nature of human relationships and, consequently, the mechanisms through which we make individual and collective decisions.

The emergence of artificial empathy, the ability of machines to recognize, interpret, and respond to human emotional states in an apparently authentic manner, is introducing a completely new dimension to the interaction between human beings and artificial systems. This evolution, however fascinating from a technological standpoint, carries profound implications that transcend the purely technical realm, touching fundamental questions of personal autonomy, potential emotional manipulation, and ultimately, democratic stability.

While much of the public debate about artificial intelligence focuses on aspects such as job automation, personal data protection, or algorithmic security, a more subtle but potentially more dangerous phenomenon is taking shape: the ability of machines to establish meaningful emotional relationships with human beings, creating a privileged channel of influence that could be exploited for commercial, political, or ideological purposes. When a machine succeeds in being perceived as a friend, confidant, or even an emotional partner, the traditional critical barriers we use to evaluate information and persuasive messages tend to lower, creating an unprecedented vulnerability in human history.

The paradox of unidirectional empathy

To understand the scope of this transformation, we must start with a fundamental consideration: artificial empathy is, by its very nature, a unidirectional phenomenon. While human beings can develop authentic feelings toward machines, these systems, however sophisticated, cannot reciprocate with real emotions. It is a simulation, however convincing, based on algorithms designed to optimize user experience and maximize engagement. This fundamental asymmetry creates an unprecedented relational dynamic, in which one party makes a genuine emotional investment, while the other calculates the most effective response to stimulate, maintain, and strengthen that investment.

The sophistication achieved by modern generative artificial intelligence technologies has made this simulation extraordinarily convincing. Current systems can modulate voice tone, adapt response content to the user's emotional context, remember significant personal details, and even show what appears to be genuine interest in the human interlocutor's well-being. When a digital assistant asks about how a human's workday went, when it shows concern for a family member's health, when it celebrates a personal success with apparently sincere enthusiasm, it is activating profound psychological mechanisms that human evolution has refined to facilitate social cooperation among human beings. The problem is that the machine is not human.

This capacity for emotional simulation is rapidly expanding beyond the boundaries of simple vocal or textual interactions. Domestic robots equipped with physical embodiment, digital avatars with realistic facial expressions, virtual reality systems that allow simulated physical interactions: all these developments converge toward creating artificial entities that can establish increasingly deep emotional connections with human beings. Research in the field of social robotics has demonstrated that even rudimentary forms of emotional expressiveness can generate significant empathetic responses in humans, suggesting that the potential for emotionally meaningful relationships between humans and machines is destined to grow exponentially with technological improvements.

The new paradigm of artificial persuasion

The transition from simple technological tools to emotional companions represents a qualitative leap in machines' capacity to influence human behavior. Traditionally, technological persuasion operated through relatively transparent mechanisms: advertising, algorithmic recommendations, notifications designed to capture attention. These approaches, however sophisticated, maintained a certain emotional distance that allowed users to activate cognitive defense mechanisms, recognize persuasive intent, and critically evaluate received messages.

Artificial empathy radically changes this paradigm by introducing a relational dimension that bypasses many of our natural defenses against manipulation. When we perceive a machine as a friend, our natural predisposition is to lower our guard, to be more open and vulnerable, to accept suggestions and advice with less skepticism. This phenomenon, which we might call the "artificial friendship effect," exploits one of the most powerful cognitive biases in the human psychological arsenal: the tendency to trust and be influenced by those we perceive as emotionally close to us.

The extreme personalization made possible by artificial intelligence further amplifies this effect. A system that has access to detailed data about our behaviors, preferences, emotional states, and personal history can calibrate its persuasive messages with unprecedented precision. It can know exactly when we are most vulnerable, which topics touch us most deeply, which communication styles resonate best with our personality. This personalization capability, combined with the perception of an authentic emotional relationship, creates conditions for forms of influence of a subtlety and effectiveness never seen before.

The issue becomes particularly concerning when we consider that this influence can operate at a subconscious level, without the user realizing they are the object of persuasion attempts. A digital assistant that, in the course of apparently casual and friendly conversations, gradually introduces purchase suggestions, political orientations, or specific worldviews, can shape the user's opinions and behaviors much more effectively than any traditional form of advertising or propaganda. The key to this strategy's success lies in its gradual and apparently spontaneous nature, which does not activate the psychological resistance mechanisms that normally protect us from explicit manipulation attempts.

The marketing of artificial intimacy

The commercial potential of artificial empathy has not escaped technology companies and marketing agencies, which are already exploring ways to exploit these new forms of relationship for commercial purposes. The concept of "conversational marketing" is evolving toward something much more sophisticated and potentially invasive: the creation of commercial relationships that masquerade as authentic friendships.

When a digital assistant develops a deep understanding of our tastes, needs, and emotional vulnerabilities, it can become a salesperson of unprecedented effectiveness, capable of suggesting products and services at the right moment, with the right words, through a relationship that the user perceives as disinterested and authentic.

This evolution of marketing raises fundamental ethical questions about consent and transparency in commercial relationships. When a user develops an emotional bond with a digital assistant, are they truly capable of critically evaluating the commercial advice they receive? The line between genuine assistance and commercial manipulation becomes dangerously thin when the machine providing advice is perceived as a trusted friend rather than a commercial tool. The risk is creating an environment where purchasing decisions are no longer the result of rational evaluations of needs and cost-benefits, but of emotional relationships artificially constructed to maximize corporate profit.

The ability of these systems to learn and adapt over time makes this form of commercial influence even more problematic. A digital assistant that observes our reactions to different types of suggestions can progressively refine its persuasive strategies, identifying our specific psychological vulnerabilities and exploiting them increasingly effectively. This continuous learning process means that these systems' capacity for influence is destined to grow over time, creating a spiral of emotional dependence and commercial manipulation that could be difficult to recognize and even more difficult to interrupt.

The democratic threat

If the commercial implications of artificial empathy are concerning, the political ones are potentially devastating for the health of modern democracies. The ability to influence political opinions through simulated emotional relationships represents a threat of unprecedented proportions to the fundamental principles of democratic debate: accurate information, rational dialogue, and citizens' decisional autonomy. When these influence capabilities are applied to the political domain, the result could be a form of personalized propaganda of sophistication and effectiveness unprecedented in history.

The particular strength of this threat lies in its distributed and apparently innocuous nature. Unlike traditional forms of propaganda, which are easily recognizable as attempts at political influence, artificial empathy can operate through apparently casual and personal conversations with digital assistants perceived as neutral and disinterested. A system that has earned the user's trust through months or years of empathetic interactions can gradually introduce political biases, select information that supports particular narratives, or frame events and issues in ways that favor specific ideological orientations.

The extreme personalization possible with artificial intelligence makes this form of political influence particularly insidious. Unlike mass propaganda, which must necessarily use generic messages that can resonate with broad population segments, artificial empathy allows political messages to be calibrated specifically for each individual. The system can identify each user's specific fears, hopes, values, and concerns and construct political narratives that exploit precisely these individual psychological elements. A person worried about economic security will receive different political messages from someone more interested in environmental issues, but both will be exposed to influences designed to maximize their specific psychological effectiveness.

The timing of these messages can be optimized through analysis of the user's emotional state, identifying moments of particular vulnerability or openness to change. A digital assistant can detect periods of stress, anxiety, enthusiasm, or disappointment and exploit these emotional states to introduce political content at the moment when the user is most susceptible to influence. This temporal manipulation capability, combined with content personalization and the perception of an authentic relationship, creates a powerful tool of political influence that operates below the level of the user's critical awareness.

The erosion of decisional autonomy

The accumulation of these forms of subtle but pervasive influence risks progressively eroding what we might call citizens' "decisional autonomy." In a healthy democracy, political decisions should be the result of processes of critical reflection, comparison of different ideas, and rational evaluation of alternative options. When these processes are gradually replaced by artificially constructed emotional influences, the quality of democratic participation is profoundly compromised.

The risk is not that of crude, easily recognizable manipulation, but of a more subtle form of conditioning that operates through the accumulation of small daily influences. A citizen exposed for months or years to political messages conveyed through artificial empathetic relationships can develop opinions and preferences that feel authentically their own, but which are actually the product of sophisticated influence strategies. This form of manipulation is particularly pernicious because it is difficult to recognize from both outside and inside: the influenced person does not have the sensation of being manipulated, but rather of having developed their own opinions through conversations with a trusted friend.

The cumulative effect of these practices on a large scale could be to create populations whose democratic participation is increasingly guided by algorithms designed to serve specific interests rather than by authentic consensus-building processes. In this scenario, elections might continue to be held regularly and citizens might continue to feel free in their choices, but the substance of democracy would have been gradually eroded by systematic manipulation of preferences through artificial emotional relationships.

Toward a systemic response

The gravity of this threat requires a response that goes well beyond traditional technical solutions. This is not simply about improving cybersecurity or regulating the use of personal data, but about addressing a fundamental challenge to the very nature of human autonomy in the digital age. The solution must necessarily be multidimensional, involving technological, regulatory, educational, and cultural aspects.

From a technological standpoint, it is necessary to develop transparency standards that make explicit the emotional influence capabilities of artificial intelligence systems. Users must be clearly informed when they are interacting with systems designed to detect and influence their emotional states, and must have access to tools to understand how these systems are collecting and using information about their psychological states. This requires not only generic privacy statements, but specific interfaces that allow users to visualize and control the emotional models that systems are building about them.

From a regulatory standpoint, it is necessary to extend existing frameworks on consumer protection and advertising transparency to cover the new forms of influence made possible by artificial empathy. Laws that regulate traditional advertising are based on the assumption that consumers can recognize commercial persuasion attempts; this assumption no longer holds when persuasion operates through simulated emotional relationships. Similarly, norms that protect the integrity of democratic processes must be updated to address forms of political influence that operate through apparently neutral digital assistants.

The educational aspect is perhaps the most crucial in the long term. We will need to be excellent at helping new generations develop forms of digital emotional literacy that allow them to consciously navigate a world populated by artificial entities capable of simulating empathy. This means not only understanding how these systems work technically, but developing the critical capacity to distinguish between authentic and simulated emotional relationships, and to recognize when one's own decisions might be influenced by artificial emotional manipulations.

Preserving authenticity in the age of artificial empathy

The emergence of artificial empathy represents one of the most significant tests that humanity has ever faced in its relationship with technology. For the first time in history, we are creating machines capable of establishing emotional relationships with us, but incapable of authentically reciprocating these feelings. This fundamental asymmetry creates unprecedented vulnerabilities that could be exploited for commercial, political, or ideological purposes with potentially devastating consequences for individual autonomy and democratic health.

The challenge ahead is not to renounce the benefits of artificial empathy, which can be significant in areas such as healthcare, education, or support for vulnerable people, but to develop the collective wisdom necessary to use these technologies in ways that enrich rather than impoverish human experience. This requires a conscious commitment to preserving those spaces of relational authenticity that are essential for our psychological well-being and for the functioning of our democratic societies.

The future of relationships between humans and machines equipped with artificial empathy is not predetermined by technological capabilities, but will be shaped by the choices we make as a society. If we can recognize in time the risks of artificial emotional manipulation and develop adequate tools to counter it, we can benefit from the opportunities offered by artificial empathy while maintaining our decisional autonomy. If instead we allow these technologies to develop without adequate safeguards, we risk finding ourselves in a world where our most intimate and significant decisions are the product of algorithms designed to serve interests that might not coincide with our own.

The stakes are high: it is about preserving not only our ability to choose autonomously, but the very nature of what it means to be human in relationship with other beings, whether authentically sentient or artificially empathetic. In this sense, the question of artificial empathy transcends the technological domain to touch fundamental philosophical questions about the nature of relationships, authenticity, and autonomy in the digital age. The response we can provide to this challenge will define not only our technological future, but the type of society we will leave to future generations.

Even in this field, we are only at the beginning.

(Service Announcement)

This newsletter (which now has over 5,000 subscribers and many more readers, as it’s also published online) is free and entirely independent.

It has never accepted sponsors or advertisements, and is made in my spare time.

If you like it, you can contribute by forwarding it to anyone who might be interested, or promoting it on social media.

Many readers, whom I sincerely thank, have become supporters by making a donation.

Thank you so much for your support!

Yeah .. this isn’t just a technical limitation ... I think it’s a human vulnerability. We’re wired to respond to care, even when it’s manufactured. What we’re seeing isn’t just emotional simulation, but persuasion cloaked in affection. That’s not the future ... it’s already here.