Three fundamental shifts in technology #77

When machines perceive, think, and act in the physical world at superhuman speeds, we're witnessing the convergence of three forces that will reshape everything.

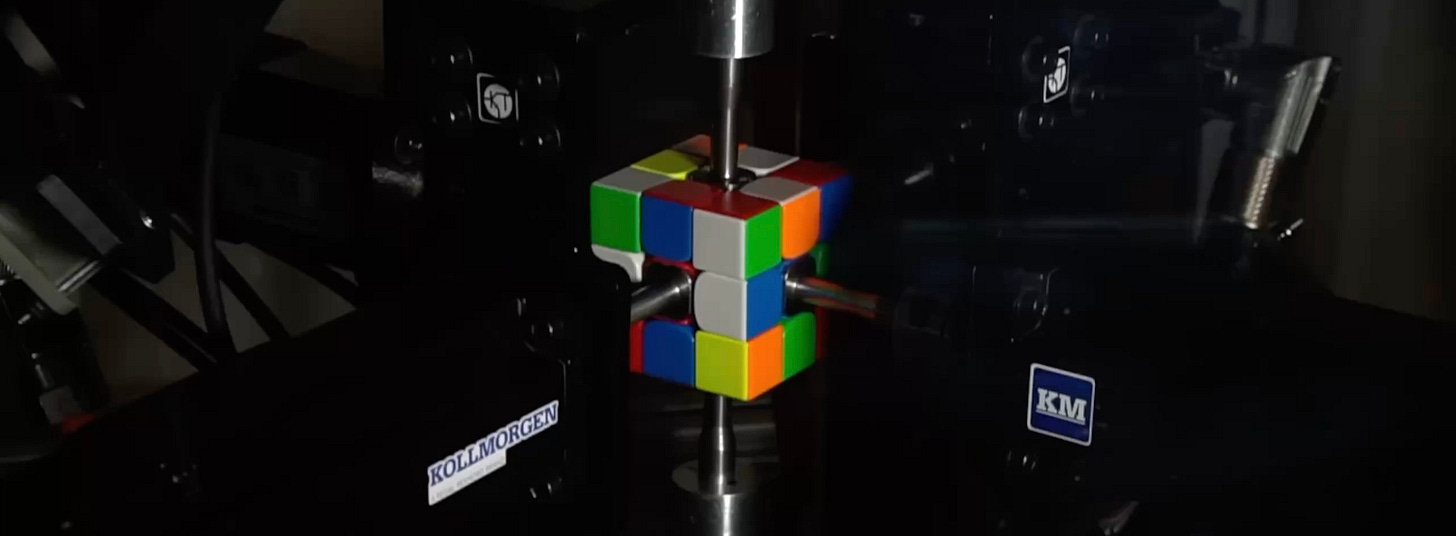

In April 2025, four engineering students at Purdue University accomplished something that defies human comprehension. Junpei Ota, Aden Hurd, Matthew Patrohay, and Alex Berta, all students at the Elmore Family School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, created “Purdubik’s Cube”, a machine that solved a scrambled Rubik’s cube in precisely 0.103 seconds, shattering the previous Guinness World Record of 0.305 seconds held by Mitsubishi Electric. To put this in perspective, the machine completed its task in less than half the time it takes to blink, which typically requires between 200 and 300 milliseconds. The human record stands at approximately 3.08 seconds,

making the machine roughly thirty times faster than the most skilled human competitor on the planet.

This achievement represents the culmination of years of incremental progress in robotic cube-solving. The journey began with CubeStormer 3 in 2014, a robot built with Lego Mindstorms and smartphone components that solved the cube in approximately 3.25 seconds. Over the following decade, increasingly sophisticated robots pushed the boundaries further, eventually breaking the one-second barrier and continuing to improve. What makes the Purdue team’s achievement particularly remarkable is not just the raw speed, but the integration of cutting-edge technologies across multiple domains that made such performance possible.

When we watch the video of this achievement, our initial reaction might be simple amazement at the speed, perhaps followed by appreciation for the engineering prowess required. However, I believe we would be making a fundamental mistake if we dismissed this as merely another impressive technological stunt. This tenth of a second actually encapsulates three profound evolutionary trajectories that will define the technological landscape of the coming decade. These are not isolated developments but deeply interconnected forces that, when combined, promise to transform how machines perceive, think about, and interact with the physical world.

When perception becomes reality

The Purdubik’s Cube achievement begins not with computation or mechanical movement, but with something far more fundamental: the ability to see and understand the physical world with extraordinary precision and speed. The system employs two high-speed cameras positioned at opposite angles to the cube, each capable of simultaneously capturing three faces. These cameras operate with exposure times of approximately ten microseconds and use deliberately low resolutions of just 128 by 124 pixels.

This might seem counterintuitive, as we typically associate higher resolution with better quality, but the engineers made a calculated trade-off that reveals a deeper truth about machine perception. Rather than reconstructing a complete image as a human might process visually, the software extracts raw data directly from the sensors and feeds it into an ultra-high-speed color recognition system. The machine doesn’t need to “see” the way humans see. It needs just enough information to make accurate decisions and take appropriate actions, and it needs this information immediately.

This represents a fundamental shift in how we think about machine perception. For decades, computer vision systems attempted to replicate human vision, building detailed representations of scenes and objects. However, machines can develop their own ways of perceiving the world, optimized not for human-like understanding but for task-specific efficiency. The evolution of sensor technology over the past two decades has been revolutionary, with sensors becoming simultaneously cheaper, more precise, more diverse, and increasingly ubiquitous.

The proliferation of sensors is creating what I call a “perceptual substrate” for artificial intelligence, a rich tapestry of environmental data that machines can use to understand and interact with the physical world in increasingly sophisticated ways. Consider that the cost of producing high-quality image sensors has dropped by orders of magnitude since the early 2000s, while their capabilities have expanded dramatically. We now have sensors that can detect everything from minute changes in air pressure to subtle variations in electromagnetic fields, from the chemical composition of gases to the precise position and orientation of objects in three-dimensional space.

The exponential increase in the quantity and quality of environmental data fundamentally changes the relationship between machines and the physical world. In manufacturing, sensor networks can monitor equipment health and predict failures before they occur. In healthcare, continuous monitoring through wearable sensors enables early detection of medical issues. In agriculture, soil and weather sensors combined with aerial imaging provide unprecedented insight into crop health and resource needs. Machines are becoming active observers and participants in the environment, capable of adapting their behavior based on real-time feedback, predicting future states based on observed patterns, and interacting with people, objects, and contexts in ways that feel increasingly natural.

Without advanced sensors, there can be no meaningful artificial intelligence applied to real-world problems. You can have the most sophisticated algorithms in existence, but if those algorithms don’t have high-quality data about the state of the world, they remain trapped in a purely theoretical realm, unable to bridge the gap between abstract computation and physical reality. This is why the sensor revolution represents such a crucial foundation for the future of intelligent systems.

When algorithms become the true multiplier

While sensors provide the raw material for intelligent action, it is algorithmic sophistication that transforms this data into meaningful decisions and behaviors. The Purdubik’s Cube must calculate the optimal sequence of moves to solve the cube in a timeframe measured in microseconds. A standard Rubik’s cube has approximately 43 quintillion possible configurations. Finding the optimal solution requires sophisticated search and optimization algorithms.

The system employs Rob-Twophase, an evolution of the Kociemba algorithm specifically adapted for robotic manipulation. This algorithm doesn’t just find any solution, it finds one that takes advantage of the machine’s unique capabilities, including its ability to perform simultaneous rotations across different planes and to execute corner cutting techniques. What fascinates me about this is not merely the calculation speed, but the way the algorithm is intimately tailored to the physical capabilities of the system that will execute it.

This represents a sophisticated form of embodied computation, where the distinction between thinking and doing becomes increasingly blurred. The algorithm doesn’t exist in an abstract mathematical space divorced from physical reality. Instead, it is deeply aware of the mechanical constraints and capabilities of the system it controls, optimizing its solutions for practical execution rather than theoretical elegance.

We are moving away from the traditional paradigm where computation happens in one place and execution happens in another. Instead, we are developing systems where perception, decision-making, and action form a tightly integrated loop, each informing and constraining the others in real-time. The time between observation, decision, and action is collapsing from seconds to milliseconds to microseconds, fundamentally changing what kinds of tasks machines can perform.

In my view, algorithms are becoming the true multiplier of value in modern technological systems. The same sensors feeding data into a poorly designed algorithm will produce mediocre results, while sophisticated algorithmic approaches can extract remarkable insights and capabilities from relatively simple sensory inputs. This is why organizations worldwide are investing so heavily in algorithmic research and development across the entire spectrum of computational sciences.

When intelligence enters the physical world

The third and perhaps most transformative aspect of the Purdubik’s Cube is that it operates in the physical world. The system physically manipulates the cube through six industrial-precision motors, one controlling each face, coordinating their movements with submillisecond timing. This represents one of the most significant shifts in artificial intelligence trajectory.

For the vast majority of computing history, computation has been fundamentally disconnected from physical action in the world. Computers process information, store data, display results, but they don’t directly manipulate physical objects. The rise of cyber-physical systems represents a fundamental break from this pattern. These are systems where computation is intimately integrated with physical sensors and actuators, creating a seamless loop of perception, decision-making, and action.

The motors employed are industrial-precision actuators capable of extremely rapid acceleration and deceleration without introducing errors. The team had to modify the Rubik’s cube itself to withstand the mechanical stresses, implementing a reinforced internal core and strengthening contact points throughout. When computation moves into the physical world, it must grapple with all the messy constraints of material reality, including friction, inertia, structural integrity, and the finite strength of materials.

This integration of computational intelligence with physical capability is not merely an interesting curiosity. It represents the vanguard of a transformation that will reshape numerous industries and aspects of daily life. We are moving toward a world where artificial intelligence will increasingly operate through physical bodies, robotic systems, and autonomous machines that can perceive, decide, and act in the real world.

The trajectory is already visible across multiple sectors. In manufacturing, collaborative robots work alongside human operators, adapting their movements in real-time to ensure safety while maintaining productivity. In warehouses, autonomous mobile robots navigate complex environments, coordinating with each other to optimize logistics operations. In healthcare, surgical robots enable minimally invasive procedures with precision that exceeds human steady-handed capability. In agriculture, autonomous vehicles equipped with sophisticated vision systems can identify and treat individual plants, dramatically reducing pesticide use while improving crop yields.

What distinguishes these emerging cyber-physical systems from traditional automation is their ability to handle uncertainty, adapt to changing conditions, and operate in unstructured environments. The Purdubik’s Cube, while operating in a highly controlled setting, demonstrates the fundamental capabilities that make such adaptability possible: rapid perception, intelligent decision-making, and precise physical execution, all integrated into a seamless whole.

I believe we are approaching an inflection point where the widespread deployment of capable robots will move from being a distant future possibility to being a present-day reality. The technical foundations are rapidly falling into place: sensors are becoming cheap and ubiquitous, algorithms are becoming more sophisticated and efficient, and the integration of these elements with precise mechanical systems is becoming increasingly seamless. The question is no longer whether such systems will become common, but rather how quickly they will be deployed and what societal adjustments will be necessary to ensure their benefits are broadly shared.

The real revolution lies in integration

(Yes, this is advertising about the importance of system integrators and technology consulting companies. 😉)

The real significance of solving a Rubik’s cube in a tenth of a second lies not in any single technological advancement but in the seamless integration of all three elements: sophisticated sensors, optimized algorithms, and precise mechanical control. The Purdubik’s Cube could not function without any one of these elements, and it is only through their tight integration that the overall capability emerges.

This principle of integration rather than isolated advancement will characterize the most important technological developments of the coming decade. We are entering an era where the greatest value comes from intelligently combining different technologies into integrated systems that can accomplish previously impossible tasks. The progression from 3.25 seconds in 2014 to 0.103 seconds in 2025 reflects advances across all three dimensions and, crucially, better integration of these elements.

In my professional experience, the most successful implementations of advanced technology are those that take a holistic, integrated approach. Companies that invest in sensors without developing the algorithmic sophistication to extract value from the resulting data see disappointing returns. Organizations that develop powerful AI systems but lack the means to deploy them in ways that affect the physical world struggle to translate computational power into business value.

What concerns me is ensuring that as these capabilities develop, they are deployed in ways that genuinely benefit humanity. The technology itself is neutral, but the ways we choose to deploy it will have profound consequences for work, economic opportunity, privacy, autonomy, and the fundamental relationship between humans and machines.

The future will be characterized by increasingly sophisticated collaboration between human intelligence and machine capability, where each brings complementary strengths to bear on complex challenges. Humans excel at tasks requiring creativity, contextual understanding, ethical judgment, and emotional intelligence. Machines excel at precision, consistency, speed, and processing vast amounts of data. The most powerful systems will effectively combine these complementary capabilities.

However, realizing this vision requires conscious effort and thoughtful design. We need to actively think about how to design systems that amplify human capabilities rather than replacing them, ensure that benefits are broadly shared rather than narrowly concentrated, and maintain meaningful human agency in a world where machines operate with superhuman speed and precision.

The story of the Purdubik’s Cube is about the convergence of sensing, computation, and physical capability into integrated systems that can perceive and act in the world with remarkable effectiveness. It is a story about how technological progress increasingly comes from intelligent integration of multiple capabilities. And it should prompt us to think carefully about the world we are building and the role that increasingly capable machines will play in that world.

As I reflect on that tenth of a second, I am filled not just with admiration for the technical achievement but with a sense of responsibility about the future we are collectively creating. We stand at a moment of genuine historical significance, where the capabilities we are developing today will shape the world for decades to come. Let us approach this moment with both enthusiasm for the possibilities ahead and thoughtfulness about ensuring that the powerful tools we are creating serve purposes worthy of their power.

BTW: My personal best on the Rubik’s Cube 3x3x3 is 57 seconds. What’s yours?

(Service Announcement)

This newsletter (which now has over 6,000 subscribers and many more readers, as it’s also published online) is free and entirely independent.

It has never accepted sponsors or advertisements, and is made in my spare time.

If you like it, you can contribute by forwarding it to anyone who might be interested, or promoting it on social media.

Many readers, whom I sincerely thank, have become supporters by making a donation.

Thank you so much for your support!

The move from isolated sensors to integrated cyber-physical systems is the key insight here. I've worked with teams building warehouse automation and the real bottleneck was never sensor quality or algorithm speed alone, it was getting those elements to actually talk to each other in realtime. The Rubik's cube example is perfect because it collapses perception-decision-action into microseconds, which forces you to confront every latency issue simulataneously. Most orgs still treat AI as a software problem when it's increasingly a hardware integration challange.