When seeming crazy is actually genius #76

Innovation often looks wrong before it works. The Apollo missions proved that a counterintuitive idea can be the most effective solution.

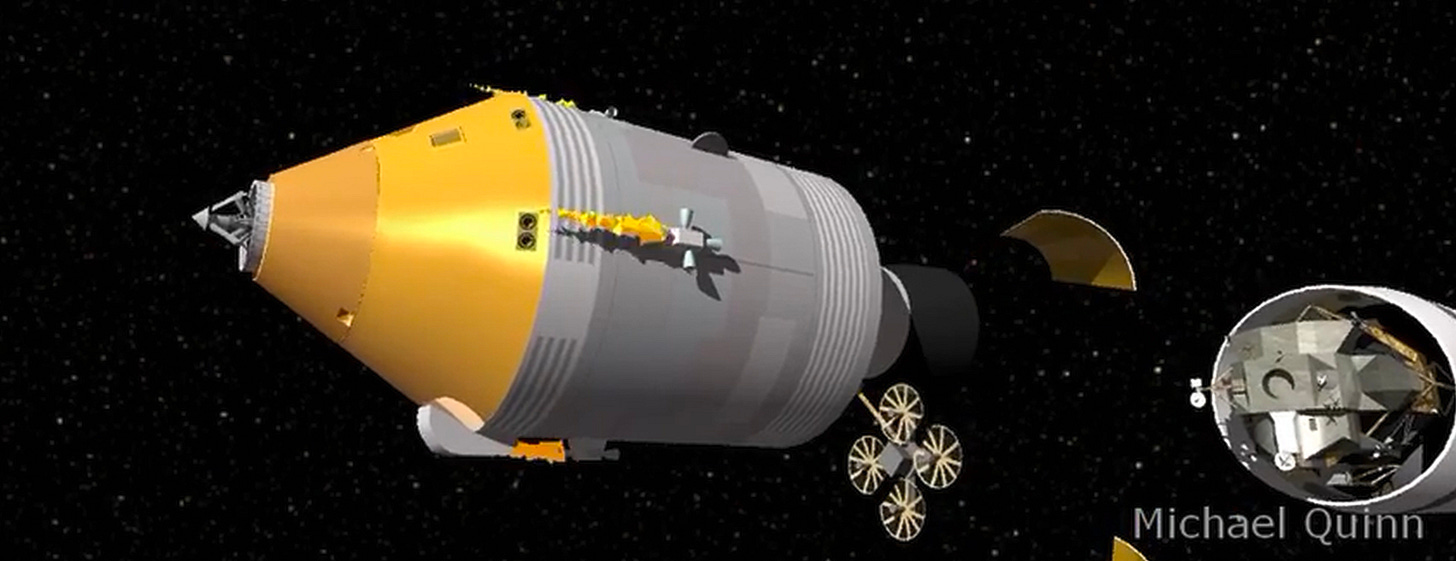

I can imagine the scene in that NASA conference room, somewhere in the early 1960s, when a group of engineers stood up to present what must have seemed like an absolutely lunatic idea to their managers. They weren’t proposing a bigger rocket, more powerful engines, or simply loading up more fuel. No, they were suggesting something far stranger: undock the command module while hurtling through space, move it away from the rest of the spacecraft, rotate it 180 degrees in the void, and then carefully bring it back to dock with the lunar module.

The silence that must have followed this proposal is almost palpable across the decades. Someone in that room certainly thought: “These people have completely lost it.” And yet, this apparently insane maneuver would become one of the most critical elements in humanity’s journey to the Moon. It’s a perfect illustration of something I’ve come to believe deeply: the most transformative innovations almost always look like terrible ideas at first glance.

The problem nobody wanted to face

To understand why this solution was so revolutionary, we need to appreciate the problem it solved. The lunar module wasn’t sitting conveniently alongside the command module where astronauts could simply float across. It was tucked away beneath, nested inside the protective shroud of the Saturn V rocket like precious cargo in a specially designed container.

Once in orbit and heading toward the Moon, this configuration presented an enormous challenge. The astronauts couldn’t just open a hatch and climb down. They needed to extract the lunar module, make it accessible, and prepare it for descent—all while traveling through space, hundreds of thousands of miles from Earth.

Think about the complexity: two spacecraft components that need to connect, positioned in exactly the wrong configuration. Traditional thinking would suggest building an internal passage, adding mechanical arms to extract and reposition the lunar module, or perhaps redesigning the entire rocket architecture. The engineers faced a problem that kept them awake at night, wrestling with a question that seemed to have no good answer: “How do we connect these two vehicles in space, safely, reliably, and without carrying along half a refinery’s worth of fuel?”

The counterintuitive solution

The solution they arrived at seemed to violate every principle of simplicity and directness. Instead of making the problem simpler, they appeared to make it more complex. The command and service module would separate from the adapter housing the lunar module, fire thrusters to move away, perform a 180-degree rotation, essentially flipping around completely, and then carefully approach the now-exposed lunar module to dock nose-to-nose.

Described like this, it’s easy to imagine the skepticism. “You want to separate our spacecraft, spin it around, and then try to dock while traveling at thousands of miles per hour through the vacuum of space? And you’re suggesting this as the safe option?” The skeptics had good reason for doubt. Space missions had been about minimizing risk, reducing complexity, keeping things straightforward. Deliberately disconnecting and reconnecting in space seemed to add unnecessary risk.

Why madness was actually sensible

But here’s what makes this story a perfect case study in genuine innovation: that apparently absurd maneuver was actually the most elegant solution possible. The alternative approaches all carried fatal flaws. Building an internal passage would have added enormous weight and complexity. Designing mechanical arms would have required motors, hydraulics, and control systems adding mass and potential failure points. Redesigning the Saturn V would have meant starting the entire rocket program from scratch.

The transposition and docking maneuver solved multiple problems simultaneously. It minimized spacecraft weight by eliminating heavy extraction mechanisms. It used existing propulsion and control systems, requiring no new technology. It provided an early test of critical docking systems when astronauts were still relatively close to Earth. And it was surprisingly fuel-efficient, those short thruster burns consumed far less propellant than any alternative.

In other words, instead of solving the problem by adding complexity, bigger rockets, more fuel, more mechanisms, the engineers completely reframed how they looked at it. The question shifted from “how do we push harder?” to “how do we use what we have more intelligently?” This is innovation in its purest form: the solution isn’t always about doing more, but about thinking differently.

Why breakthrough ideas always seem wrong at first

This brings me to something I’ve observed throughout years: truly transformative ideas almost always seem wrong at first. They appear complicated, risky, or simply foolish when you first encounter them. The human mind is wired to prefer familiar patterns and linear solutions. When someone breaks these patterns, our instinctive reaction is skepticism or dismissal.

I believe this is why so many breakthrough innovations face initial resistance. It’s not that people are unimaginative, it’s that genuinely novel solutions require us to suspend immediate judgments and work to understand why they might be correct. The lunar docking maneuver required NASA’s leadership to trust their engineers’ calculations over gut reactions, to have faith that something looking more complicated was actually simpler.

The pattern repeats across fields: vaccination seemed insane until it proved itself. Open-source software contradicted security common sense until it demonstrated robustness. Free products with advertising revenue seemed financially suicidal until Google proved it worked. Eventually, innovations become so established that people forget they ever seemed strange. Young engineers today learn about the docking maneuver as a clever solution, never fully appreciating how radical it must have seemed when first proposed.

The personal challenge of championing counterintuitive ideas

A couple of years ago, as we were preparing for a meeting, the CEO of the company I worked for asked everyone on the team to bring something personal that represented who we were and our attitude. The story of the moon landing immediately came to mind. It perfectly captured what I believe innovation truly is: the willingness to pursue solutions that initially seem to be going in the wrong direction.

So I launched enthusiastically into my explanation, describing modules spinning in space and maneuvers that appeared to be moving backward. I painted the picture of those NASA engineers proposing their “crazy” idea, and how that craziness turned out to be genius.

But as I spoke, I noticed something deflating: most of the expressions around the table remained politely perplexed. Those faces that say “interesting... but we didn’t understand any of that.” Maybe I explained it poorly, getting too caught up in technical details. Or perhaps, when you’re accustomed to linear solutions and straightforward thinking, counterintuitive ideas just don’t land the way you hope. Nobody had an epiphany. Nobody shouted “Great story!”

But here’s what I took away: the best ideas often need time. They need context. They need someone willing to persist in explaining them, to find different ways to make the connection clear. They can’t be measured solely by short-term business. Sometimes they’re just insights that should be considered for their beauty and the impact they can generate.

This is the challenge of organizational innovation: how do you create an environment where people seriously engage with ideas that initially seem wrong? How do you develop the patience and trust necessary to evaluate counterintuitive proposals fairly?

Lessons for today’s innovation challenges

The lunar docking story offers specific lessons for contemporary innovation. First, the best solution isn’t necessarily the most obvious one. Breakthroughs often emerge from reframing the problem entirely. NASA engineers didn’t ask, “How do we carry everything to the Moon in one piece?” They asked, “What if we assemble the mission in space?”

Second, it shows the value of working backward from constraints. The engineers had strict limits on weight, fuel, reliability, and development time. These constraints didn’t stifle innovation, they channeled it. By accepting what couldn’t be changed, they focused creative energy on finding solutions within those parameters. Too often, people treat constraints as barriers when they should be guidelines directing innovative thinking.

Third, it demonstrates the importance of testing wild ideas rather than dismissing them out of hand. The maneuver could have been ruled out immediately as too risky. Instead, engineers ran calculations, built simulations, tested systems, and gradually proved it would work. This willingness to seriously evaluate unconventional ideas is crucial for innovation.

Finally, it shows that innovation requires courage. The engineers who proposed this solution, and the NASA leadership who approved it, had to defend an approach that looked dangerous and overcomplicated. They had to withstand skepticism and maintain confidence even when common sense seemed to argue against them. This courage, the willingness to advocate for ideas that seem wrong, is perhaps the scarcest resource in innovation.

Creating space for counterintuitive ideas

When I think about today’s challenges, whether in business, technology, or sustainability, I see the same patterns. We’re constantly confronted with problems that seem to require straightforward solutions: just do more of what we’re already doing, but bigger and faster. But what if the real solutions are counterintuitive? What if addressing climate change requires economic models that initially seem to work against traditional growth? What if business success comes from focusing on fewer things more deeply rather than expanding in all directions?

I’m convinced that many of our most pressing challenges await solutions that will initially seem wrong. Someone, somewhere, is probably working on an idea right now that would solve a major problem but seems too strange or too risky to be taken seriously. The question is whether we’ve created environments where such ideas can surface, be evaluated fairly, and be implemented despite their initial strangeness.

This requires genuine intellectual curiosity at the leadership level. Leaders need to be interested in understanding why an idea might work, not just whether it fits their existing mental models. Organizations need forums where unconventional ideas can be presented in depth, not just in elevator pitches. Some ideas require walking through the problem, the constraints, the alternatives, and the logic to make sense.

There should be explicit encouragement of dissenting views and genuine safety in proposing ideas that challenge established thinking. The moment people learn that unconventional proposals are career-limiting moves, innovation dies. This doesn’t mean every strange idea deserves implementation, but it does mean every strange idea deserves serious consideration.

So the next time you encounter an idea that seems wrong, that appears to be going backward when you think you should be going forward, pause. Ask questions. Try to understand the reasoning. Because maybe, just maybe, you’re looking at the next innovation that will seem obvious in hindsight but courageous in the moment.

After all, every breakthrough idea is someone’s “crazy” proposal that just happened to work.

And you?

Are you equipped to seize the great opportunities presented by counterintuitive ideas?

(Service Announcement)

This newsletter (which now has over 6,000 subscribers and many more readers, as it’s also published online) is free and entirely independent.

It has never accepted sponsors or advertisements, and is made in my spare time.

If you like it, you can contribute by forwarding it to anyone who might be interested, or promoting it on social media.

Many readers, whom I sincerely thank, have become supporters by making a donation.

Thank you so much for your support!